30 Years After Stephen Lawrence

While the wake of Stephen’s murder led to police reform and a criminal justice system review, it didn’t lead to institutional change.

On the 30th anniversary of the murder of Stephen Lawrence, we delve into whether it's time to consider that police reform hasn't cured institutional racism and if abolition is the way forward.

Who was Stephen Lawrence?

Stephen Lawrence was a Black British teenager from Plumstead, South-East London. He was part of a loving family, which included his parents, Doreen and Neville, brother Stuart and sister Georgia.

Stephen wanted to harness his talents for maths, art and design to pursue his dream of becoming an architect. He was studious but had an active social life which he juggled with family commitments and part-time employment.

On the evening of 22 April 1993, around a month before I was born, Stephen’s life was cut short by a racially motivated attack. He was murdered while waiting for a bus in Well Hall Road, Eltham when he was 18 years old.

The aftermath

Stephen was murdered in an unprovoked racist attack by strangers. After the initial investigation, which has been accused of being fraught with corruption, five suspects were arrested but not convicted. In 1994, Stephen’s parents launched a private prosecution against three of the suspects; two years later, this failed to yield results.

In July 1997, a public inquiry into Stephen’s case was held, which led to a police investigation. This inspired the publication of the Macpherson Report in 1999, which accused the Metropolitan Police of institutional racism. The report put forward 70 recommendations; all centred on police reform.

In the years ahead, the Lawrence family never gave up hope in holding those responsible for Stephen’s murder. In 2005, Double Jeopardy, the legal principle preventing suspects from being tried twice for the same crime, was scrapped.

It would take Doreen and Neville 16 years until the murderers of Stephen were put to trial. Two of the original suspects, Gary Dobson and David Norris, were found guilty of Stephen Lawrence’s murder and were handed life sentences.

What was the Macpherson Report?

The report came about due to the relentless campaigning of the Lawrence family. There were a series of events that happened before the report was published, including:

- Following the dropping of charges against two of the suspects, Jamie Acourt and Neil Acourt

- The collapse of a private case by the Lawrence family

- The announcement of an investigation into the case by the Police Complaints Authority, the then Home Secretary, Jack Straw, announced the establishment of an inquiry into Stephen’s murder

The Mcpherson Report was administered by Sir William Macpherson, a retired High Court Judge and former Soldier, who was appointed Chair. Advisors on the report were:

- Tom Cook, a retired Deputy Chief Constable

- Dr John Sentamu, the Bishop for Stepney

- Dr Richard Stone, the Chair of the Jewish Council for Racial Equality

Not a single member of the inquiry had lived experience of anti-Black racism.

The 350-page report laid bare what Black communities had known for a long time: the Metropolitan Police was “marred by a combination of professional incompetence, institutional racism and a failure of leadership”. Specific officers in the Metropolitan Police were named, and the entire force was criticised.

The report’s authors stated that the inquiry had transformed the debate about policing and racism “and that the debate thus ignited must be carried forward.”

What was the impact of the Macpherson Report?

The report put forward 70 recommendations, with 67 of these leading to specific changes in practice or the law within two years of its publication.

The changes included:

- The introduction of detailed targets for the recruitment, retention and promotion of Black and Asian officers

- The creation of the Independent Police Complaints Commission (IPCC), now known as the Independent Office of Police Conduct (IOPC), with the power to appoint its own investigators

- The abolition of the ‘double jeopardy rule’ - which eventually led to the 2012 conviction of Gary Dobson and David Norris for Lawrence’s murder

The Macpherson Report may have positively impacted how racially motivated cases are handled by the Metropolitan Police. However, Stephen’s murder and the recent Casey Report show that the Metropolitan Police is still steeped in institutional racism, misogyny and homophobia.

The Casey Report, officially known as The Baroness Casey Review, was commissioned by former Police Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, Cressida Dick, following the murder of Sarah Everard by former Police Officer Wayne Couzens.

Findings from the Casey Report refute Dick’s claim that problems in the Met are limited to a few bad apples. Theoretically, a few bad apples lead to the entire basket being rotten. The review echoes the Macpherson Report and former Police Commissioner Robert Mark in 1972, when he expressed that he had “never experienced … blindness, arrogance and prejudice on anything like the scale accepted as routine in the Met”.

This begs the question: if we are having the same discussions as in 1972, does police reform actually work? Or does it, in fact, lead to more funding being allocated to an already corrupt system, helping officers escape responsibility and accountability for their actions?

What was the impact of Stephen Lawrence’s murder on British society?

The murder of Stephen Lawrence sent shockwaves across the world and had a generational impact on Black people and communities - this includes me. I wasn’t born when Stephen was murdered. I didn’t move to England until 2004 and spent most of my childhood in Sweden. But in my early teens, I remember switching on the TV and watching a documentary about his murder. I was distraught; it was the first I learned about how racism can manifest into violence.

I didn’t know him or his family, but I felt like he was a part of me because Stephen could have been my father, brother or friend. His murder could have happened to anyone with Black skin. He did not know his murderers, and they did not know him.

As the Casey Report has demonstrated and the murder of Joy Gardner, Mark Duggan, Rashan Charles and more recently, Chris Kaba, our generation is still plagued by institutional racism within the Metropolitan Police. Our criminal justice system still fails Black people because it was not made with us in mind or with safety and harm prevention at its core. The history of the British olice stems from the idea of quelling dissent and protecting the interests of landowners.

While the wake of Stephen’s murder led to police reform and a criminal justice system review, it didn’t lead to institutional change. The bad apples mentioned in the Macpherson Report were still at work long after publication. The Casey Report has not instigated any other police officers being fired.

Alongside this, the impact of Stephen Lawrence’s murder lifted the veil on racism in the UK, not for Black and racialised people but for white people who had turned a blind eye to racism. Politicians and police officers alike, as much as they tried to deny that institutional racism reverberated through the Met, couldn’t deny they had failed the Lawrence family and that this was a result of racism.

The changes to Britain’s legal landscape following the murder of Stephen may not have happened had it not been for the Mangrove Nine in 1968. This was the first time the judiciary recognised evidence of racial hatred within the Metropolitan police toward the Black communities of London.

The Macpherson Report redefined racial incidents and obliged the police to investigate every incident that the victim believed to be racially motivated. Heavier penalties mean the courts recognise that crimes motivated purely by hatred differ. The extension of such ‘hate crimes’ to cover attacks motivated by somebody’s religion, sexuality, disability, or gender has also increased public confidence in the willingness of the police to tackle this kind of crime.

However, hate crime legislation is born from police reform and may not lead to true justice. Some social commentators and prison and police abolitionists have expressed that ‘hate crimes’ are used to increase the public’s confidence in the police without actually bringing about institutional change. Some see it as a band-aid solution for something that needs much deeper attention.

Generational trauma

Stephen Lawrence’s murder put the spotlight back on the Metropolitan Police. Much like the murder of George Floyd, people were horrified by not only the murder but the failure of the police to hold the primary perpetrators to account. The murder of Stephen was reminiscent of the murder of Emmett Till, a 14-year-old Black American who was murdered in 1955 after being accused of offending a white woman, Carolyn Bryant, in her family’s ‘grocery store’. Carolyn Bryant is alive today and still hasn’t been held accountable for the part she played in Till’s murder.

Trauma is passed through generations of Black people. We are united by trauma. George Floyd’s murder highlighted this when it was reported that Iberia Hampton, the mother of murdered Black Panther leader Fred Hampton, used to babysit for Emmett Till.

If not police reform, what then?

“All my skin folk ain’t my kinfolk" - Zora Neale Hurston

Zora Neale Hurston said it best, and we’ve seen this statement proven time and time again. More recently, this idea has been cemented with the appointment of Rishi Sunak as the Prime Minister of the UK, Kemi Badenoch (Equalities Minister), the former Home Secretary Priti Patel, and current, Suella Braverman, and former Chancellor of Exchequer Kwasi Kwarteng.

One of the recommendations of The Macpherson Report was to increase the racial diversity of people officers in the Met. At the time of its publication, only 2% of officers in the police service were from a Black and global majority background. Responding to the report, the then-Home Secretary, Jack Straw, set a 10-year target for improving representation. In March 2020, 11 years after, this target was met.

According to the Independent Police Complaints Commission (IOPC), less than one in five staff members come from a racialised background, despite the organisation’s claims it is proactive about understanding discrimination. Their website states” “We are delighted to launch the IOPC EDI Strategy 2022-25, and underpinning EDI policy – which outlines our commitment to the development of a more empowered and inclusive workplace - and improved services for all.”

Equality, Diversity and Inclusion practices do not go far enough in rooting out institutional racism and discrimination. The recommendations put forward by the Macpherson Report have proven this. Recently the Metropolitan Police has been running an aggressive advertising recruitment campaign to persuade more Black and racialised officers to join them.

This does indicate that the issue isn’t about representation. The issue concerns power and how we treat communities experiencing marginalisation in this country and beyond. The increase of Black and global majority police officers hasn’t decreased police violence or the overrepresentation of Black and racialised people in the criminal justice system.

The Macpherson Report and the Casey Report reveal that it’s “more of the same” and that “nothing much has changed” since Stephen Lawrence was murdered 30 years ago. Police reform has proven to be a failure time and time again. How can you reform an institution which is rotten to its core?

The Macpherson Report also led to the inception of the IOPC. However, the IOPC is anything but independent as it’s funded with grant aid by the Home Office. It also provides the majority of funding to the Metropolitan Police and other police agencies across the country under the police funding settlement.

Between 2020-2021 out of the 460 investigations completed by the IOPC, 107 misconduct proceedings were brought forward, with only eight officers and staff having faced criminal proceedings. Out of these, only six officers pleaded guilty or were found guilty at trial.

According to the Casey Report and as reported by the BBC, 1,809 officers of all those facing allegations - had more than one complaint raised against them, with 500 facing between three and five separate misconduct cases since 2013.

The team behind the report have said “less than 1% of officers facing multiple allegations had been dismissed from the force, with one continuing to serve despite facing multiple serious allegations - including corruption, traffic offences and “failure to safeguard while off duty.”

With countless reports on Met Officers' misconduct, why aren't investigations being brought forward? Why are officers not being held accountable?' This may be due to its attachment to the Home Office and the Metropolitan Police as a result. Since ex-police officers and staff work at the IOPC, it’s not able to be genuinely independent and free from bias.

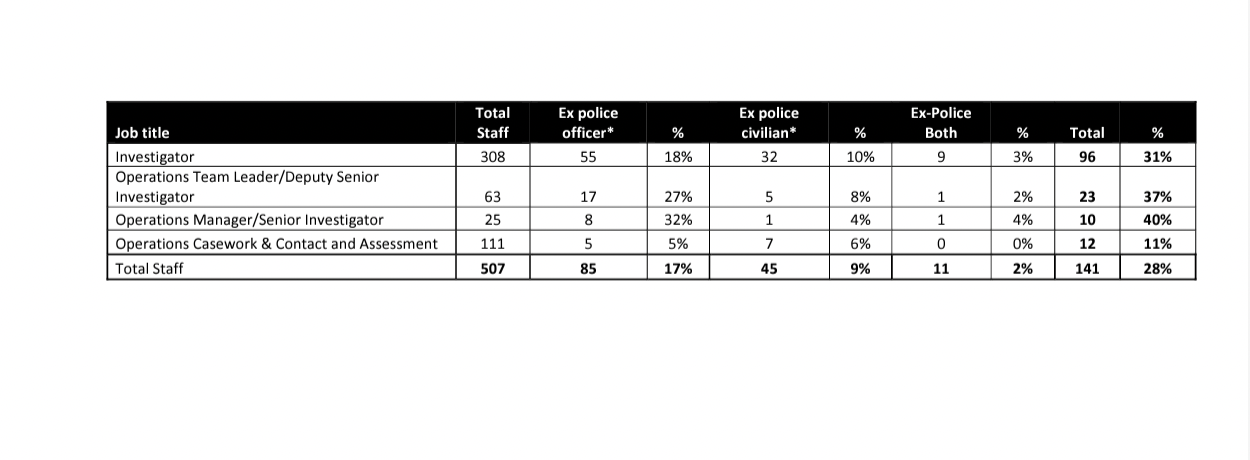

According to a Freedom Information Request put forward by Peter Thompson in 2019, this is how many ex-police officers and staff work at the IOPC:

In 2021, a parliamentary inquiry found that little has changed since the Macpherson Report and that the IOPC remained “too complacent on matters of race”. The IOPC has shown that its complaints system is still failing victims of police discrimination; only 2% of complaints of discriminatory policing were actually upheld between 2019 and 2020.

Since 2020, we’ve been having more frank conversations around the issues of policing. During the Black Lives Matter uprisings following the murder of George Floyd, the conversation started to move from police reform to defunding the police, to abolishing the police in its entirety.

Abolitionist thinking is about getting to the root of the issue, pulling it from its core and starting again. Abolition of police and prisons looks at establishing harm prevention, harm reduction and transformative justice. It’s about recognising that harm or - as the state brands it, ‘crime’ - is a societal issue. This often stems from poverty, in regards to poor housing or a lack of housing, inadequate healthcare or no access to healthcare, lack of food, clothes and poor or lack of education.

Police reform never looks at what leads people to commit harmful acts, but abolition does. It’s time to recognise that police reform will not protect us, but abolition might.

Read more on policing, abolition and legal rights:

- Know Your Rights: Strip Searching of Children

- Give Chris Kaba the Same Energy You’re Giving Queen Elizabeth II

- How We Process Emotions Following the Trial of George Floyd’s Murderer

- Five Tools to Empower You: Race and Your Legal Rights

- 2020: The Year We Took a Stand

This piece was written by Educator, Campaigner, Content Creator and Spark & Co.’s Brand and Engagement Lead, Zoe Daniels (They/Them). Find out more about them here.